🐌 “I look at my peers, and they’re all directors and VPs. Am I behind? Will I risk being seen as unambitious?”

🪜 “My VP’s feedback is always through the lens of performing at the next level [director], but I’m happy where I am, which is frustrating.”

🐢 “I can’t help feeling like my career has stalled. I’m ten years in, and I’m still an individual contributor (IC). But I like my job and want to keep doing it.”

💔 “As a director, I’m constantly jealous of the product managers on my team. I wish I was still doing their job, and I regret being promoted. I realize there’s very little ‘product’ to the job: I’m mostly a bureaucrat. But I can’t be seen as stepping backward.”

😔 “I have a collaborative, humble, and lead-from-behind style. This is incompatible with the hard-charging ‘own the room’ behavior that is valued in directors at my company. Soon I’ll be forced to choose between tapping out or trying to become someone I’m not.”

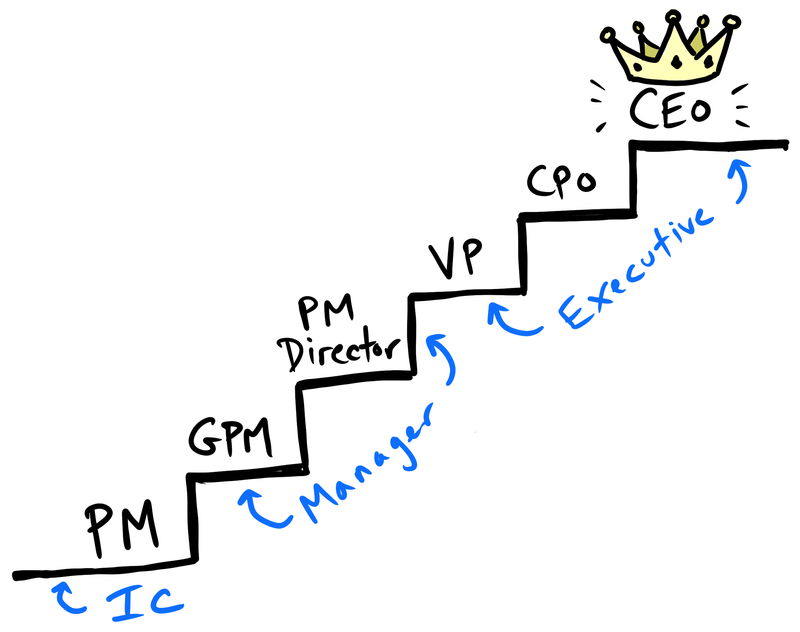

These are statements I’ve heard from coaching clients, friends, and colleagues over the years. The pandemic has accelerated this trend as many more product managers begin to look inward and confront the ways in which their careers aren’t aligned with what brings them fulfillment. I empathize because I felt exactly the same way, especially after reaching the group product manager (GPM) level at Google. The discomfort is because the widely assumed career path for PMs is quite simple and looks something like this:

Presumed product manager career path

There are other variations for sure, maybe becoming a general manager with P&L responsibilities or continuing as a CPO but at increasingly more consequential organizations. But the expectation is always that you keep moving up. Product management has largely been seen as an intermediate step on a route to something loftier. Satisfaction with anything less is indicative of a lack of ambition.

But what happens if somewhere along the line you discover that you’re climbing someone else’s ladder or just that you’re done climbing and happy to stay on your current rung? What if you really love being a product manager and want to do more and better product work? And let’s not overlook those who choose a balanced life outside of work or would like to start a family or leave the profession for a while to become a primary caregiver to a child or loved one.

This mindset is incompatible with the up-and-up march toward CEO. To many of our observers, anything less is tantamount to failure. Few of us started our careers in product management. We had to work tremendously hard to get the job to begin with, which makes this CEO hustle peer pressure so exhausting. We had to swing over to this ladder from another one: from engineering, business analysis, customer success, marketing, or wherever. To many, becoming a product manager was the achievement, and now we’re expected to keep on marching? What if this is our destination?

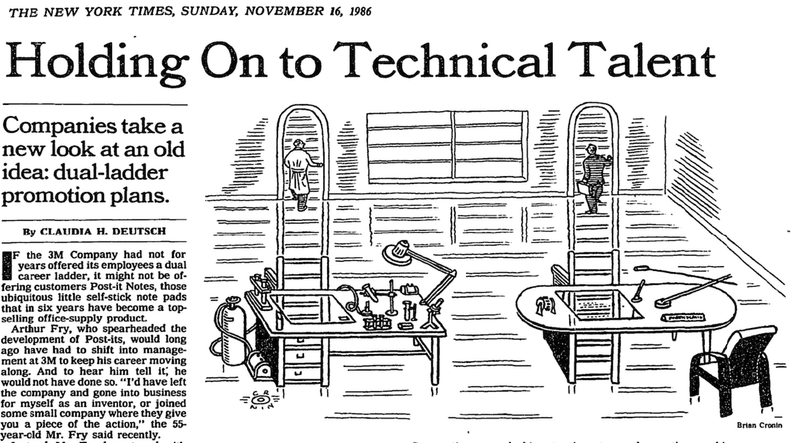

Decades ago, engineers confronted executives about these same concerns. Corporations discovered that you couldn’t pressure high-performing individual contributors in engineering or scientific roles to keep climbing a people management ladder if they didn’t want to. You end up losing talented people and stacking your leadership ranks with reluctant, incompetent people managers (the so-called Peter Principle).

Here’s a New York Times article from 1986:

“We are trying to avoid situations where people who excel technically feel compelled to seek management positions to advance,” said M. Frank Squires, vice president of research operations and personnel at Xerox’s Corporate Research Group. American companies have always wrestled with ways to keep the Peter Principle at bay — to prevent competent salesmen, for example, from rising to become incompetent sales managers. The obvious answer was to create a parallel promotion track whereby outstanding performers could get the same money, recognition and perks as managers — without taking on any managerial responsibilities.

Well, duh.

Furthermore, most engineering and product design career progression frameworks have at least an informal career level — that is, the terminal rung at which it’s completely acceptable to say, “I’m done moving up; I’m happy spending the rest of my working life right here.” So, why is it different for product managers?

Some tech companies do have at least partial dual career ladders, exemplified by a principal product manager role. Curiously, some of the oldest software companies are among them (e.g., Microsoft, Oracle, and Intuit). But this product management job title is more the exception than the norm. Searching LinkedIn, I found 1,200 people in the San Francisco Bay Area who currently have the job title “Principal Product Manager,” compared to nearly 10,000 with variations of the “Director of Product” title. A whopping nine have the title “Distinguished Product Manager.”

I’ve heard complaints from employees at these companies that the principal level is not really equal to the management rung. The gravity is still toward the people management side of the ladder, with the principal role considered a second-class citizen. One of their employees told me, “They only created [the] principal [level] to avoid having to pay any more director salaries.”

When I was a GPM, I asked a Google senior vice president responsible for product manager career development why Google didn’t have dual ladders for product managers. Despite PM ladders mirroring Eng (and Design) in many other ways, why did we have principal software engineer and principal designer roles but no principal product manager? Their response was, “It’s hard for a product manager to be an individual contributor since a lot of product management work at the senior level requires managing a team.”1

I immediately regretted my phrasing — it’s not as simple as an IC vs. manager framing. At the time, I was managing several people. Like me, most of the people who faced this career conundrum were happy being people managers and were even enjoying it. And, of course, product managers at every level are expected to demonstrate leadership.2 Many of the quotes at the beginning of this article come from outstanding people managers who love leading teams, coaching others, and nurturing talent. What they don’t like is when the “management” part of their job begins to drown out the “product” parts.

As for me, I recalled the days of my engineering management career when I was responsible for hundred-person organizations and realized that it brought me little satisfaction. A full 90% of my job was people management and everything else that went with it. Worse, the expansion of my responsibilities left me with minimal time to shine at the parts of management I enjoyed the most. For example, I was a much better coach and career mentor to three direct reports than I was to 20. As your department’s headcount and business surface area grows, you spend more of your day managing up and sideways than managing down. (Less charitably: bureaucracy and politics trample coaching.)

Was it possible to grow as a product leader but to do so in such a way that the majority of my job didn’t comprise people management (and its associated burdens)? I wanted to be a product manager, not a ᴘʀᴏᴅᴜᴄᴛ MANAGER. Could this be possible?

I surely hope so. I first wrote about this topic in 2016. But I want to tackle the issue more aggressively today since I’m aware of more than one Silicon Valley tech company that is reconsidering its product management job framework in the face of burnout and high post-pandemic attrition. So I’d like to use my bullhorn to help companies get it right.

To move toward dual product management career paths becoming a reality, we need to establish some core principles upfront:

Product management isn’t merely a stepping stone; it’s a career. Indeed, it can be an excellent launchpad for general management and entrepreneurship. But we should also permit PMs to see it as a fulfilling journey in and of itself. Working with a team to build winning products is pretty damn rewarding. These PMs worked hard and expended considerable effort to become product managers in the first place, and we should continue to recognize their excellence by giving them opportunities to keep growing as product managers with increasingly larger complexity and impact.

My proposal isn’t a choice between managers vs. individual contributors. No PM is wholly an individual contributor — PM’ing requires leadership at all levels. But product managers on lower rungs of the ladder are certainly tasked with more execution than leadership. A better framework examines three components: IC vs. people management vs. product leadership. (See Pat Kua’s Trident Model of Career Development for a helpful framework.)

People should be encouraged to design careers that align with their values and help them find fulfillment. We should accept that some people won’t want to become CEOs or founders. Why does everyone have to be a CEO?

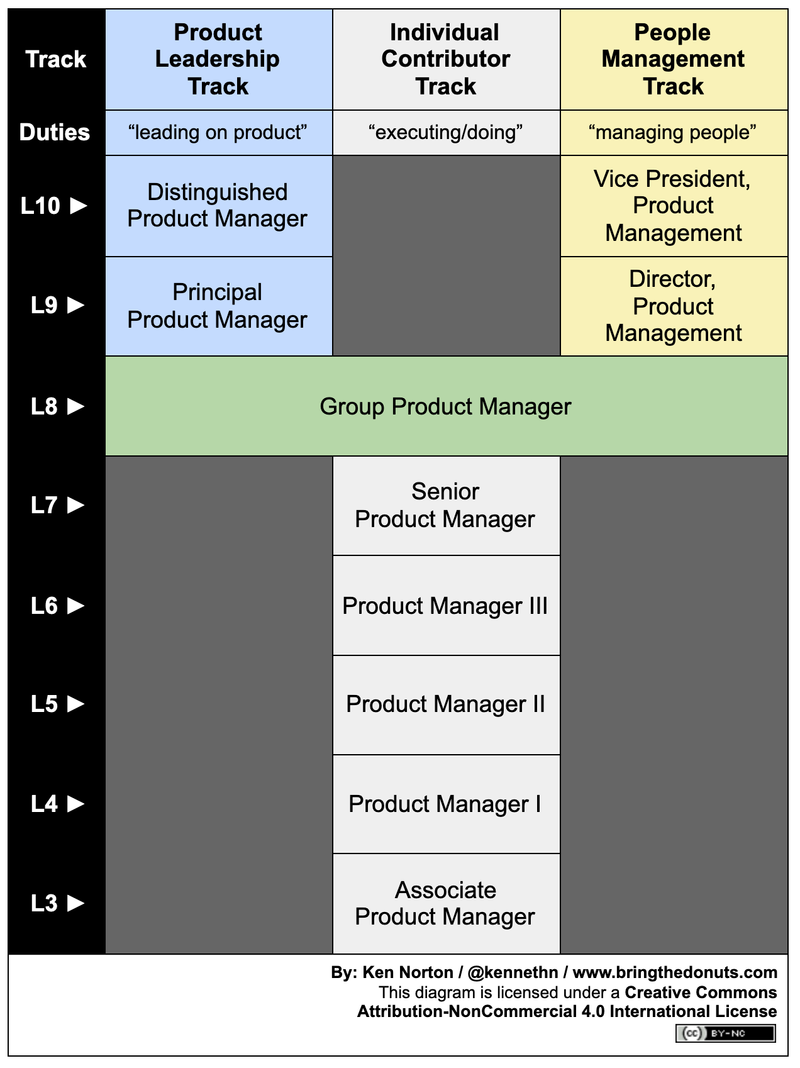

What might a multitrack product management ladder look like? If I were starting a company tomorrow, I’d use a framework like this:

A PDF version of this image is available: Product Management Job Ladder with Dual Career Paths

Now we’re talking! The first thing that stands out for me is why I loved the group product manager role so much and why it’s possibly the most underrated job in product management: It’s conceived as the perfect balance of people management and product leadership. It’s a player-coach role that lets you try before you buy — a little from Column A and a little from Column C. (The green illustrates the blend of the blue and yellow paths.)

GPMs are expected to manage other PMs, but not a large number, and no more than would allow you to continue allocating the majority of your energy to product work. GPMs should be encouraged to explore both aspects of the role and to decide the best next step for themselves without judgment.

It might be acceptable for them to decide that they love being GPMs and to remain in this role for the rest of their careers. But if they want to proceed up the ladder, they can now choose between doubling down on people management or continuing as product leaders. Again, this choice is personal and is likely to be guided by what brings them day-to-day joy and the direction in which their longer-term careers are heading.

By the way, from a talent retention perspective, it should be good news that PMs are looking for alternate paths. There can be only so many directors and VPs on a given ladder, especially at companies that aren’t doubling or tripling in size every year. As one leader at a company with dual ladders put it, “If you only offer the manager path, by definition, the majority of your GPMs will leave because leverage ratios won’t enable them to stay.” Dual ladders create more growth and retention opportunities than would be found on the scarce manager path alone.

Here’s how I roughly define the three key roles at the product management career fork:

Group Product Manager

- 40% people management (staffing the team, setting objectives, making decisions, resolving escalations, career guidance, coaching, and organizational design)

- 20% individual contributor (hands-on execution: discovery, roadmapping, writing, delivery/shipping, etc.)

- 40% product leadership (inspiring and motivating the team, product vision, product strategy, internal and external evangelism, product mentorship, and discovery)

- Between one and five direct reports, ideally no more than three to begin with

- Common career paths: continuing as GPM, director of product management, or principal product manager

Director of Product Management

- 70%+ people management (staffing the team, setting objectives, making decisions, resolving escalations, career guidance, coaching, and organizational design)

- ≤30% product leadership (inspiring and motivating the team, product vision, product strategy, internal and external evangelism, product mentorship, and discovery)

- Between eight and 20 direct reports, also likely to be a manager of managers

- Common career paths: VP product, chief product officer, general manager, CEO

Principal Product Manager

- ≤30% people management (staffing the team, setting objectives, making decisions, resolving escalations, career guidance, coaching, and organizational design)

- 70%+ product leadership (inspiring and motivating the team, product vision, product strategy, internal and external evangelism, product mentorship, and discovery)

- Between three and five direct reports or a larger number of more senior reports

- Common career paths: continuing as a principal, distinguished product manager, chief product officer, founder, venture capitalist

- Owns a large product area or strategic “pillar” — that is, builds on the GPM role with the same management responsibilities but with more scope, higher-profile products, and a more significant cross-organizational impact

- This is not an IC role!

You might ask why a principal spends a smaller percentage of their time on people management compared to a GPM despite a principal having the same or a larger number of direct reports. This is because the GPM is still learning the people management ropes, and we want to give them space to focus on strengthening those skills through training, coaching, and practice. It’s hard to learn how to delegate execution without delegating the success of the product.

Of course, all of the percentages are merely estimates and open to interpretation; they will fluctuate with product launches, growth stage, the pace of hiring, and the like. There’s also considerable overlap between director and principal, and this is absolutely by design. The gist is that one role is more people management than product leadership, and the other is more product leadership than people management.

Titles and levels vary across companies, so this precise terminology may not be an exact fit for you. I’m sure many other variations might work as well, so feel free to tailor. Here are some possible modifications:

-

GPMs and principals are peers on the ladder, and the split between the two paths starts a level earlier. Many of these organizations have director and senior director rungs on their ladders, which has the added benefit of creating room for another product leadership level (perhaps one where the prestigious “fellow” is a peer to VP). Fundamentally, this is roughly the same model, but with the titles moved around. Still, it might be a better fit for certain ladders, especially ones whereby senior product managers have people management responsibilities.

-

The product leadership–people management split is even more extreme for principal product managers: 80%–20% or even 90%–10%. Principal PMs may manage only one or two people or may have no managerial responsibilities at all. It might work in cases in which the PM is genuinely uninterested in people managing or where the product surface area they’re responsible for is more forward-looking or strategic, and there’s not yet a need for direct reports. It might also be a good fit for cross-organizational strategic roles without dedicated teams (e.g., responsibility for driving ML adoption across the entire company or a product privacy czar). It’s important to note, however, that despite having minimal to no people management responsibilities, this still isn’t a heads-down IC execution role; it’s a product leadership role.

-

In early-stage companies, the director role — or even the VP of product — might have job duties comparable to a principal. In a smaller startup, a director of product management might only manage a handful of folks because the team is so small. As a result, the job might look more like a principal with a majority of time focused on product leadership over people management. This is often why PMs feeling uneasy with management overhead at big companies are attracted to director or VP positions at startups. (A friend calls this “promotion downsizing” — a better title with fewer direct reports.) This is fine, but it’s important for the individual to have clarity about their preferred career path before the company outgrows them and they find themselves on the wrong ladder.

-

Ladders can allow for lateral movement. Someone can spend time as a director and then decide that they’d like to switch to the other ladder, becoming a principal. Many engineering ladders offer this mobility. I like that this provides flexibility over the course of a career, especially as someone’s interests and passions evolve. This might get tougher the higher up the ladder one goes: The managerial skills that got someone promoted to VP may not come with the sophisticated product leadership chops needed to operate as a distinguished product manager. Lateral mobility can also address the startup situation above, allowing that early-stage director to migrate to a principal role as the team grows too big for them to want to manage.

If you agree with my arguments, I hope you’ll join me in pushing for dual career ladders in product management. Product management has matured and is long overdue for the same treatment that our technical colleagues have received for decades. Most importantly, one’s base compensation, bonus, and equity should be comparable no matter which path one follows. Nobody should have to sacrifice earning potential if they forgo the people management track to focus on product leadership. And most importantly, no one should ever feel like they have to give up doing what they love in order to advance in their career.

Thanks to Hunter Walk, James Raybould, Rachel Wolan, and two unnamed coaching clients for providing feedback on drafts of this article. Also a special thanks to all of the individuals who are paraphrased at the top and who’ve helped shape my thinking on this topic. You know who you are, and you’re awesome. Keep doing what you do.

Recommended Reading

- The Career Dilemma: Hunter Walk’s advice to product managers: “Ultimately, if Google had created a product track that gave me a chance to influence the product’s future direction, without necessarily having to be responsible for three dozen people and the politics associated, maybe I would have moved into that role as opposed to leaving.”

- Product Management Career Ladders at 8 Top Technology Firms, Sachin Rekhi

- The GPM Role, Marty Cagan

-

Google still doesn’t have a principal PM role or anything above that, and to the best of my knowledge, it’s never been seriously contemplated. I would most likely still be at Google today if my proposed job ladder existed at the company. I would have loved nothing more than to retire from Google as a distinguished product manager. The only way to become the equivalent of a principal PM at Google is to get promoted to director or VP, decide you don’t like politicking and managing huge teams, ultimately burn out, and still have the clout to be allowed to go off to an island by yourself with no (or few) direct reports to work on “special projects.” (👋 to all my friends who have done this.) ↩

-

Somewhat curiously, many of the principal engineers, distinguished engineers, and engineering fellows I knew at Google were managing people too. So the crisp “IC vs. manager” distinction doesn’t always hold true in engineering either. ↩