Iremember countless evenings as a teenager in the 1980s when I’d retire to my family’s Apple ][+ computer after dinner. I’d excitedly jump back into a BASIC program, feverishly coding away at some problem. Then, what seemed like only moments later, mom or dad would be tapping me on the shoulder and grumpily pointing at the clock: four o’clock in the morning, long past time for bed. How had that happened? I seemed even more awake and energized now than I was hours ago!

We all can think of moments when we were so engrossed in an activity that the concept of time seemed to disappear. We’re “in a zone,” effortlessly riding a wave of hyperfocus at the intersection of challenge, pleasure, and skill. Despite the intensity of deep concentration, the work becomes its own reward, and we gain energy. As one coaching client described it, “there is somehow more of me afterward than there was before.”

In the 1970s, psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi was the first to name this phenomenon: flow. Csíkszentmihályi described flow as an activity with clear goals and progress, immediate feedback, and with a strong balance between the perceived challenge and one’s perceived skill.

![[Chart: Challenge Level vs. Skill Level. Flow lies at the intersection of High Skill and High Challenge.]](/generated/img/newsletter/challenge-v-skill-800-23605b069.png)

But there’s a bit more to the story. Only some challenges that come up against our talent and skill level can lead to a state of flow. Unfortunately, some tasks lead us in the other direction: burnout.

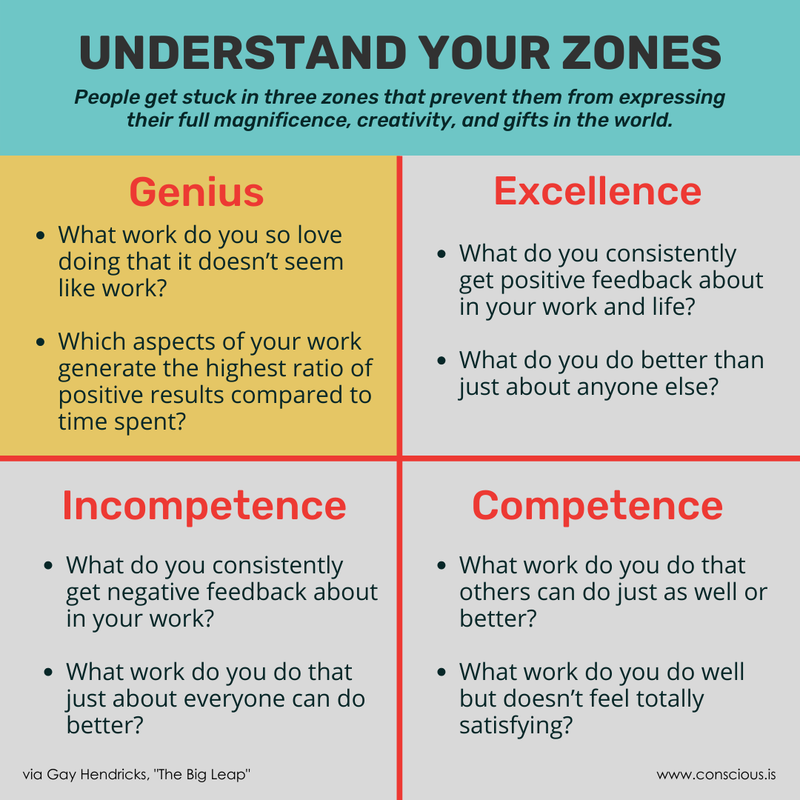

One of the most valuable concepts I use in my coaching to help us understand this difference is the Zone of Genius, based on the work of Gay Hendricks. The word “genius” might sound a little pompous and egotistical, but Hendricks deliberately used the term to reinforce that everyone is a genius at something. To Hendricks, the Zone of Genius is the intersection of talent, skill, and passion: what we are good at that also gives us energy. It’s not enough to be good at it. It must also bring you pleasure and joy.

One of my clients once taught me the Japanese concept of Ikigai (生き甲斐), which is another name for the same thing: the intersection of what we love, what we’re good at, and what the world needs.

This all seems so simple until you meet the Zone of Genius’s crafty neighbor, the Zone of Excellence. The Zone of Excellence includes things we might be extremely good at—maybe amongst the best in the world—but that don’t bring us joy or pleasure. In fact, they slowly drain our energy and lead to dissatisfaction and burnout.

Understanding the difference between the Zone of Genius and the Zone of Excellence is especially important for leaders (the other two zones: the Zones of Competence and Incompetence, tend to be a bit more obvious). The world slowly pushes us into our Zones of Excellence. Early on, we may even confuse Excellence for Genius, especially when praise and regard from our bosses and peers is the intrinsic reward that motivates us.

Most promotions are ways to give leaders even more responsibilities in their Zones of Excellence. Again, these are activities that we’re tremendously good at, possibly the best in our companies. Why wouldn’t the company want you to do more of those things? But if a leader isn’t careful, they can unconsciously drift into the Zone of Excellence at the expense of living in their Zone of Genius. Over time the dopamine hit of respect and reputation dissipates, and we begin to recognize that our passion is slowly evaporating.

Further, the Zone of Excellence feels like work, whereas the Zone of Genius often doesn’t. Genius is effortless, and we’d often do those things for free if we could. Our guilt is another force that keeps pushing us away from Genius into Excellence. It can feel like cheating to be in our Zone of Genius, maybe even unfair to others.

Reclaiming your Zone of Genius requires first understanding what it contains. The best way to do that is to stop evaluating your work based on what you’re “good at” and ask, “what am I good at that also gives me energy and deep joy?”

One simple exercise is an energy audit. Reflect on the past week and make an inventory of everything you did and how you spent your time. Your calendar is an excellent place to start, but don’t forget to also include unscheduled activities and ways you spent time outside of work. For each task, rate it on the following scale:

↑ this task increased your energy

— this task was neutral (neither increased nor reduced your energy)

↓ this task drained your energy

What do you notice about the types of activities that give you energy? What might be in your Zone of Excellence: you’re asked to do it, you’re good at it, yet it leaves you depleted? Are you able to drop or delegate some of these tasks? Perhaps these tasks might live in someone else’s Zone of Genius, how might you learn that?

It’s also helpful to get feedback from others. Ask people who know you well and have experienced you at your best:

- What am I doing or talking about when you experience me most energized and happy?

- When you experience me at my best, what am I doing?

- What are your favorite qualities or skills you see in me?

As leaders, we commit to operating as much as possible from our Zones of Genius, but we also take a stand for everyone around us to be able to do the same. As managers, how can we help those we lead to uncovering their own genius? Where are we steering others into their Zones of Excellence in ways that might serve the short-term interests of ourselves or the company at the long-term cost of the individual?

As Jim Dethmer puts it:

Genius equal juice. The more we live and work in our genius, the more the juice of life is flowing around us into the world. As many have said, it is not our failure that we are most afraid of but our magnificence. Conscious leaders face the fear of stepping fully into their magnificence. They embrace their magnificence, live and work in their genius, and give their gift to the world.

Further Reading

- The Big Leap and The Genius Zone by Gay Hendricks

- Flow by Mihály Csíkszentmihályi

Adapted from The Conscious Leadership Group.

Photo by Cory Schadt

-

John Geirland, “Go With The Flow: Mihály Csíkszentmihályi Interview”, Wired, September 1, 1996. ↩